Published: 23.06.2022

Painter, photographer, restorer and curator. Tomáš Lahoda of the Faculty of Restoration links his name with the university gallery GU:, which opens with a new name and content. It will offer an insight into the contemporary Czech art scene as well as exhibitions of foreign artists.

Why should a university have a gallery?

A university should present itself to the public not only through the achievements of students and researchers, but also through art. Not only for students and staff, but also for the public it is a great opportunity because they can get a glimpse of what is happening on the art scene. Universities in the United States routinely have their own galleries. In Denmark, schools even have their own picture collections. Universities buy art and have their own very valuable collections. Paintings decorate their buildings so that students and staff have access to quality art. It is an opportunity for universities to present themselves to the public and build their image and brand.

Who would you like to exhibit in GU:? What is your concept?

It will be high-quality artists. I want to create a gallery that is of a high standard and worthy of a university. I will mainly include Czech artists, but I have a vision of also showcasing some foreign artists. It will be contemporary and modern works, which is still considered classical media. The gallery will focus on paintings and photography, and to a lesser extent on three-dimensional objects and sculptures.

You are an active artist yourself; will visitors be able to see your works as well?

I would like to exhibit my work here alone or together with photographs by another particular artist. I see a certain connection between the themes of his black and white photographs and the themes of my series of large format colour paintings of the LaGuardia series. They are similar in theme, so it would be interesting to do a juxtaposition of the two.

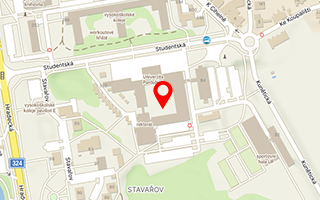

The site adjacent to the University Library, where the gallery is housed, has changed. What changes have been made there?

The gallery was this strange little corner behind the library. There were strange panels and display cases, and a glass corner facing the street that wasn't much to work with. We created some new walls with colleagues from the University, which made it quite a large space, and we installed diffused lighting. My goal was a minimalist, clean gallery separate from the library, and I think we succeeded.

There will be several exhibitions at GU: per year. How does the installation process work?

When an agreement is reached with an artist, the transport of the artwork must be arranged. The artist packages the works, a transport company comes to pick them up, and brings them to the gallery. They're unloaded, unpacked, and then the artist and I set them up along the walls. We will spend the whole day trying to find a suitable location for each piece so that the installation follows a certain logic and dynamics. When the placement is complete, the works will be hung. We also need to make sure that the works are insured so that we are covered in case of theft and damage. It could happen that someone accidentally punctures a canvas or knocks a painting off the wall. And then we just have to organise the opening.

Who do you think the gallery visitors will be?

The gallery will also be open to the public, so it would be good if not only students and staff of the University would visit it. I believe we will build a gallery that will gain a good reputation, which will attract other artists and with them other visitors. I would also like to bring our students from the Faculty of Restoration to GU: – to bring them here instead of my lectures and give them a talk related to the works on display in the gallery. I would also like to invite some of the exhibitors to give lectures or workshops for our students as well. Among other things, I plan to exhibit works that will be interesting and problematic for the students from a restoration point of view, which is often the case with contemporary art.

Why is contemporary art problematic from the point of view of the restorer?

The old works are mostly on canvas or wood, so there's no problem there. In contemporary art almost anything is used, and the material itself often has meaning. It can't just be substituted for another, because that would change the meaning of the work. Some works are meant to age and change over time, which is why materials are used that, for example, fall apart. To replace them would be to go against the intention of the artist. These are modern materials that were not originally intended to be used in art, for example, industrial paints, which change very quickly, or foam, which starts to change colour in a year and then crumbles in a few years. Such cases are common. What to do? This is a very topical issue in contemporary art restoration.

What themes do you focus on in your work?

I am interested in a variety of topics that are very different from each other. I work in series, so a certain theme always runs through the whole series. The individual series seem to be completely different projects with their own language. However, these sometimes almost contradictory styles, genres and ways of working with different themes are bound together by a unifying concept and internal logic of a few dominant interests and strategies.

In one series you reflect on consumer society and the interpretation of advertisements. What do you depict in it?

I became interested in advertising when I was living in Denmark and teaching in Brno. I flew back and forth every week for five years, so I spent a lot of time at the airport. While waiting, I flipped through magazines and realised that more than half of the content was ads. A lot of it was for perfume and fashion accessories. In addition, each product is accompanied by a face – mostly a woman's. I came up with the idea of doing a series of perfume ads, which I called Ad Paintings. I told my young daughter to draw something based on an ad. I decided to combine in the paintings the double vision of the same subject: my version with the approach of my little daughter. Then, when I started photocopying the ads, I accidentally shifted and the faces came out all messed up. It was ruined, yet strangely photogenic. I was interested in the ugliness and beauty of it at the same time. The faces were distorted and ugly, yet you could see that they were beautiful women. The bottles and lipsticks are very primitive in my series, because I took them from my daughter. The familiar perfumes become a bizarre evening dress in a distorted mirror of today's world.

There are also deer in your works. Why is that?

The series ironically refers to classical salon painting and the wide production of decadent art. The theme of the bugling deer is the prototype of kitsch. I wanted to make a series with deer that was not just another kitsch one, but serious. I had a distant relative who was an amateur deer hunter. I used his photos as a starting point and tried to put deer back on the pedestal where they belong. They are my most dimensional images. The largest measures almost six metres wide and less than three metres high. It was bought by an IT company and the deer now hangs in their headquarters.

Where in the world can your work be found?

When I was exhibiting the deer in New York, a limo pulled up and a guy got out. He looked at the exhibit and said: "I'm buying this, here's your cheque and send it to Utah, I have a cottage there." So, one ended up in a wooden cabin and one was bought by an Italian woman who took it to Italy. A lot of my work hangs in Denmark, where I lived. Many of them I don't even know about, because they might be resold after a while. When my daughter started high school in Denmark, she came home one day and said, "Daddy, we have your painting hanging in our school." In Denmark there is an institution called the Danish Arts Foundation, which buys art and distributes it to state institutions. So, one of my works is hanging in Copenhagen City Hall, for example.

In addition to artistic work, you are also involved in restoration. Recently you helped with the restoration of the Knights' Halls at the Pardubice Castle. What was your task?

That was quite a challenge. There are restored frescoes and large parts of them are missing. The job was to paint the three missing frescoes as paintings that would be a reconstruction of what the frescoes might have looked like. They were to complete all the missing scenes. It was clear that these were high quality frescoes probably based on Cranach. For example, they depicted a figure whose face and part of her hat were missing, so we first filled in the hat, the face, the missing elbow and even the necklace, because we reconstructed her from a similar lady by that artist. In another scene, for example, there was only a row of heads with a nose and a hat, and the rest was completely missing. There were no whole figures. In such cases I had to search for engravings of groups with similar hats from the same period and try to fill in the figures.

What are you working on now as a restorer?

I am restoring a large-format Renaissance portrait of Marie Lichtenstein from the portrait gallery of Mikulov Castle, and a completely repainted Baroque portrait of a nobleman from the portrait gallery of the Museum of Jindřichův Hradec Region.