Published: 04.05.2020

Plague, cholera, typhus, smallpox. These diseases at the time were killing the inhabitants of all continents. Like the current COVID-19, which struck a hundred years after the eradication of the Spanish flu. The gauze mask became a symbol of that time. Vladan Hanulík, an expert in the history of medicine at the Institute of Historical Sciences, Faculty of Arts, University of Pardubice, says that it was not the healthiest or wisest who survived in epidemics. It was a coincidence or a favourable combination of genes.

The media compare the 1918-1920 Spanish flu with COVID-19. Can any parallels be found between them?

They can, although the disease is caused by a different type of virus. However, the causes of complications in patients are similar. In the case of the Spanish flu, in addition to the usual manifestations of the infection, there were secondary complications - bacterial pneumonia, which resulted in a high number of victims. The infectivity of the flu was massive, the wave of the epidemic in cities usually lasted only three to four weeks, yet it infected one third of the world's population. However, if there were no complications in the form of secondary pneumonia, the infected persons recovered very quickly.

Where did the Spanish flu virus come from?

From Kansas, where they recorded the first cases of a flu epidemic in March 1918. The United States was already actively involved in the First World War at that time, in April 1918 the disease spread to Europe and China, along with troops from overseas. In no time, however, it engulfed the world, and to this day the wave of the epidemic is seen as a pandemic with the largest number of infected people in the history of the planet.

Why the "Spanish" name?

The "Spanish flu" name began to be used due to the fact that Spain, as one of the few European countries, did not participate in the fighting of World War II. Therefore, its representatives had no reason to hide the number of infected or statistical reports of victims for strategic reasons. War demagoguery, an attempt to conceal real data about the spread of the disease, led the uninitiated public in other European countries to believe that the epidemic had a massive effect, especially in Spain, hence the Spanish flu.

How many people died of it?

It is estimated that at least half a billion people became infected in two years, with the population of the entire planet at that time being 1.8 billion. Residents of Europe and the United States were clearly better equipped to deal with the fatal consequences of the disease, with mortality rates below 1 percent of those infected. By contrast, people in Africa, Australia and Asia were much worse off, with mortality exceeding 5 percent, and Western Samoa, for example, with a mortality rate of 23 percent.

What animal was it transmitted from?

Until recently, experts did not even know the exact form of the virus. Medical science could not isolate it a hundred years ago. From the 1990s onwards, research into the bodies of victims, which have survived to the present day due to the Alaskan frost, began to bring a breakthrough. In 2005, the gene sequence of the virus was published and the principle of the infection was clarified - it was transmitted to humans from birds. However, it is uncertain whether the outbreak originated in the United States or began to spread from China.

I deliberately asked where the disease had spread from. We often hear now that most diseases have come to us from China.

Such opinions are only partially close to reality. Epidemics spread mainly in civilizations, where there was a high concentration of large numbers of people and animals, most often domesticated. If we look at the economic weight of individual countries in the history of our planet, we will find that for most of the known history, the world economy has been dominated by Chinese and Indian civilizations, which we in Europe like to forget.

Until the 19th century, China's and India's regions accounted for about 75 percent of global economic output, and Europe and the United States got temporarily ahead them through industrialization and colonialism. To put it exaggeratedly - at a time when in China and India they drank tea from magnificent porcelain sets in a cultured way, we in the Czech lands were still making a living by hunting wild boar game. Therefore, it can be explained that many epidemics did have their origins in Asia. In addition to some influenza and coronavirus epidemics, plague, which first spread to humans about 2,000 years ago in southern China, probably also had roots here.

We treat just like 100 years ago

Were there any "emergency" measures a hundred years ago?

There were, even similar to those that apply to us today. In the USA and some European countries, public institutions, schools, churches, restaurants were closed. The gauze mask used when moving in public became a sign of the times. However, quarantine proved to be an ineffective measure at the time, and the infectivity of the disease was too high.

Was there no effective treatment then?

There was not. Even today, we do not yet know the effective targeted treatment of COVID-19, we do not know how to use drugs to prevent the virus from spreading in the patient's body, and therefore we treat it by similar means as then - bed rest, ample water/fluid intake and suppression of symptoms in the form of fever.

So, what does modern medicine give us in addition?

We have antibiotics available that can be used to treat secondary problems in the event of inflammation. However, COVID-19 causes complications in a different way. We are able to put on ventilators and oxygenate the blood through the extracorporeal circulation. As in 1918 and 1919, however, we do not yet have the most important thing - effective prevention of the spread of the disease. This will only be the vaccine serum.

Did people criticize the regulations at the time?

For the general public, the Spanish flu was a reason to criticize the therapeutic helplessness of the medicine of the time. We do not yet see similar sceptical considerations, although apart from ventilators and population testing, the Ministry of Health has so far relied more or less on a form of quarantine prevention. So basically, a medieval strategy that we have known and used since 1377. I would expect state authorities to approach the smart quarantine much earlier. We have even renounced to a large extent another weapon of modern medicine - advanced diagnostics, because we do not have enough tests. When you call a public health authority saying that you have been abroad and have a fever and cough, they will not test you, but will recommend you to rest and wear a mask.

By contrast, doctors are now portrayed in the media as fighters defending the progress of civilization. I wonder if we realize in two to three months that we should be more grateful for the peaceful survival of the whole epidemic to the saleswoman in the market, who (not equipped with any effective means of protection) was selling fruit and vegetables all the time. And thanks to the purchased vitamins, not only did we fight off the infection in peace, but with the bottle of wine that we added to the healthy diet in our baskets, we finally survived the nervousness from the media presentation of the epidemic.

Let's not panic

Today, mostly elderly or sick people die of coronavirus. The Spanish flu also took young lives. How come?

This is still unclear. Epidemics usually affect the population in a way that can be described as a statistical curve of victims similar to the letter U. Vulnerable are the youngest groups in the population who are not yet sufficiently immune, and the oldest groups whose immunity is no longer sufficient to fight the disease due to age.

However, the Spanish flu epidemic took the form of the letter W, with the main peak in mortality in groups between 18 and 35 years. The phenomenon is most often explained by the fact that the elderly had been immunized by an influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1889. Thus, older people had acquired immunity while adolescents, on the other hand, had an organism capable of withstanding possible secondary complications in the form of pneumonia.

Coronavirus has caused panic. Did people experience a similar fear of diseases and illnesses in the past centuries?

I'm afraid we're experiencing the biggest panic right now. If we understand the meaning of the word panic in its true meaning, i.e. as a disproportionate, irrational and distinct emotional response to an external stimulus, often accompanied by high internal tension. Although the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be below one percent of those infected, predominantly in people with previous serious health complications, the media world convinces us of the constant danger that is supposed threat everyone.

The influence of the media on the dissemination of information is immense.

Sure. Modern media existed to some extent, for example, as early as the beginning of the spread of cholera in the 1930s. In the Austrian Empire alone, millions of people died of the disease during the 1870s. But do you know any cholera column or monument? Cultural memory is therefore crucial. But when we compare the traces left by the plague and cholera in the collective memory, the role of this disease seems to be insignificant.

It wasn’t the healthiest who survived during epidemics

How did the Spanish flu epidemic finally come under control?

The gradual remission of the epidemic was not due to contemporary medicine. The disease spread in two waves - the first wave in the spring of 1918, the second from the autumn of 1918 to the spring months of 1919. It is likely that the disease was so infectious that other waves did not find a sufficient number of spreaders and a large part of the population was immune to the influenza strain. In addition, influenza viruses are tied to the seasonal occurrence, so the third wave did not appear.

But other diseases emerged…

Of course. However, infectious diseases became a marginal phenomenon during the first half of the 20th century. They had been replaced by diseases often resulting from abundance and lifestyle - cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, lung cancer, or diseases that are associated with older age and the resulting dysfunctions of the body, Alzheimer's disease, cancer. Nevertheless, immunologists still lived in fear of another dangerous pandemic.

Despite the high number of victims, the current COVID-19 pandemic is rather an unpleasant test of our preparedness. Estimates of mortality are still very inaccurate as we do not have data on the overall prevalence of the disease across populations. Thus, while mortality is currently reported to be between 3–6 percent, this is a proportion that is likely to decrease significantly once the epidemic has subsided. We only have reports about test subjects, and patients with more severe symptoms are mainly tested. It can be a useful lesson for us in the future. As it turned out, areas such as Hong Kong and Taiwan were able to cope with the spread of the disease by having to deal with the previous SARS epidemic.

There are less than 8 billion people in the world. Does nature itself select healthy and strong individuals from the sick? Can we observe in history that when the number of people increased, there was a plague?

If that were the case, mankind could not be so numerous now. The idea that once in a while nature sets its mind on assembling a new form of the virus just to reduce the Earth's population is rather the essence of the faith of some individuals constantly predicting various forms of civilizational collapse.

In the epidemics, it was not the strongest, healthiest or wisest who survived. It was a coincidence, or a favourable combination of genes. In the case of epidemic diseases, mutually remote civilizations came into contact that did not have immunity to widespread diseases of foreign cultures. Those who were genetically better adapted to the disease survived, which does not mean that they were adapted to all diseases. The next epidemic could bring them to the grave.

Plague as the worst infection

But people were especially scared of the plague, weren’t they?

That’s right. Therefore, the plague, returning many times since 1346, remains synonymous with epidemics. However, the word panic is misplaced here, the fear was justified. For four centuries, it aroused justified horror and conditioned the manifestations of behavioural contagion. In European cities, we have repeatedly seen mass migrations from the affected areas to the countryside.

We all carry the plague thanks to our cultural memory. Almost every city has a plague column, literary works are intertwined with the theme of plague epidemics. That's why many people invoke images of "black death" in the word pandemic.

Was the plague really the most insidious disease ever to scourge Europe?

For Europeans, the plague was truly the most terrible. It kept scourging the continent's inhabitants in repeated waves from the middle of the 14th century for 400 years. However, the plague spread across the Earth and gradually reached an estimated number of over 300 million victims. Thus, in the absolute number of deaths, no disease has yet overcome the plague.

However, the Czech lands were only marginally affected by the largest plague epidemic, ravaging Europe between 1348 and 1352. We were more affected by the epidemic of 1380. Some historians relate the given wave of epidemic influence to an increase in religious sentiment, which then resulted in the Hussite movement in the Czech lands. Church leaders eagerly proclaimed that the disease was a divine punishment, and during the epidemic, crowds of repentant flagellants (self-torturing people) marched through the towns.

Why was the plague so deadly? Was it really mainly about hygiene?

The doctors had no idea what was causing the disease. At first, the miasma theory prevailed (miasma means bad air). Thus, doctors insisted that the disease was transmitted with putrefactive particles of decaying animal bodies, natural remains and other impure elements. That's why rooms were fumigated and people had to wear masks with herbs. Hence the famous plague doctor's mask, made in 1619 by Charles de Lorme, personal physician of King Louis XIII of France.

It was not until the 16th century that opinions emerged that the epidemic was caused by so-called contagia, small bodies that are transmitted between people. However, no one definitively proved the theory. The uncertainty about the pathogen led to therapeutic helplessness. If you have no idea what causes the disease, how can you successfully treat it?

Quarantine and immunity were most effective

So, what did they do then?

Cordons sanitaires proved to be the most effective measure. That is, the restriction of movement of people and goods on the borders with foreign countries, or with the centre of infection. It was a quarantine measure that had had its tradition since 1377, when comers suspected of the potential spread of the plague were locked away in Dubrovnik for the first time in a 40-day quarantine (from the word quaranta - forty).

In what cycles did the plague return?

Picture a Pardubice-sized city - a plague disease killed a third of the population in the first year of its spread, but many of the population survived the disease and become immune. That is why the disease did not manifest itself so massively in the following years. However, the missing third of the population had to be replaced, so people came from the suburbs and the countryside, but they were not immune. So, the next wave came after several decades with an increase in their number, and it was the new immigrants and their descendants that died. As a result, the numbers of plague victims gradually decreased until a sufficient part of the population was immune. Then the plague stopped spreading. Other epidemics behaved in a similar way.

Can coronavirus stop spreading in the same way?

It is possible. The responsible authorities are only trying to reduce the impact of the first wave, because we have a limited number of beds where patients can be cared for.

Modern times have also been affected by smallpox. When were the biggest pandemics?

Smallpox manifested itself in antiquity and was also probably one of the reasons Athens lost against Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, the Athenian city-state was decimated by this airborne epidemic in 430-427 BC. Subsequently, the epidemic returned in several waves. Around 189 AD, smallpox exterminated 10 percent of the Roman Empire's population - historical sources often mistakenly refer to smallpox epidemics as plague outbreaks.

Colonizers from Europe, who provided people with blankets previously used by infected people, sometimes deliberately contributed to the spread of smallpox and the subsequent extermination of the Native American population. Thus, smallpox was actually a peculiar biological weapon used by Europeans to seize control over the continent, albeit mostly unknowingly.

How did it spread in our environment?

In the 18th century, it replaced the fear of the Black Death, and rightly so. Throughout the 18th century, smallpox dominated the epidemic waves, and even before the vaccination began, there was an epidemic spread of smallpox, which caused the death of 114,769 people in Moravia and Silesia alone between 1796 and 1812. Thus, smallpox was a "modern plague", which not even the rulers escaped - our emperor Joseph I died due to infection in 1711, Russian Tsar Peter II in 1730, and also Maria Theresa became infected with it, who then had two of her descendants variolated.

What was the smallpox mortality rate?

In modern times, the disease spread mainly in areas where general vaccination did not take place. Still, even in Europe, there was a great epidemic between 1870-75. The wave of the disease began in France, where vaccination against smallpox was not mandatory and a third of the population therefore did not undergo it. Therefore, smallpox strains survived here endemically, which we would have no longer found in other parts of the continent. The Prussian-French War was a crucial element as captured French troops spread the epidemic in what was to become Germany, while other parts of the German army became infected in France.

Was the situation different in Prussia?

Prussia was a country with a sophisticated vaccination system, France was not, so there was a big difference in the effects of the disease. While 125,000 French soldiers became infected, 28,000 of whom succumbed to the disease, only 8,500 soldiers of the Prussian army became infected and only 400 people suffered fatal consequences. From the army, the epidemic then spread to civilians and further to all countries of the continent. However, the affected were mainly those unvaccinated, or those who underwent vaccination a long time ago, which then led to an improvement in the system of re-vaccination in diseases where the immunizing effect decreases over time. No wonder, half a million Europeans have succumbed to the epidemic.

Later, thanks to a more consistent approach, smallpox epidemics spread mainly outside the European continent, but even in the 20th century, 300-500 million people died of smallpox. Their eradication (introduction of vaccination) in 1977 is therefore an important milestone for humanity.

People were dying of smallpox even in the 20th century. Does history show us that vaccination makes sense?

When current hyper-modern medicine encounters a new type of disease, it sometimes suddenly reaches the level of 19th century medicine - before the invention of antibiotics and antivirals. Thus, the only effective weapon of modern medicine is a vaccine serum to immunize our body. It may now be appreciated even by those who otherwise criticize vaccination. Vaccination, together with antibiotics and sanitation of life, is the most effective tool of modern medicine. Only thanks to it are we now dealing with high blood pressure and obesity rather than the spread of scarlet fever, whooping cough, tetanus and other diseases.

Simply put, until the discovery of antibiotics, medicine had virtually no weapon for targeted treatment - it only suppressed the symptoms of disease. Our civilization is built on vaccination, and it is perhaps a good thing that the new virus has now reminded us of it in such an unpleasant way. The refusal to vaccinate in contemporary Czech society is rather the result of a special type of selfish liberalism in which we do not take into account the safety of others.

Suppose you refuse, as a mother, to have your daughter vaccinated against smallpox. The daughter grows up and at the age of thirty she wants to conceive the next generation. However, she comes into contact with an infected child of a friend who did not have her child vaccinated. The result is a high risk of deformation of the foetus, i.e. the future baby of the expectant mother. Do we really want to go down that route?

Toward the future, what could COVID-19 inspire us to do?

Maybe to formulate a new survival strategy. It turns out that mutual consideration is the key. In the context of coronavirus, the media and politicians use terms that refer metaphorically or directly to war and combat deployment.

In reality, however, the spread of disease will be prevented by the calming of our civilization habits and consideration for others. When you walk down the street, try to strip away the masks and the presence of the disease and think about whether you would actually want to live permanently in a similar environment. After 20 years, you can suddenly ride the streets with your children without the threat of being killed by anyone every minute. Our consumer needs have been reduced to basic food and IT resources, which we use to remotely keep in touch with our loved ones and co-workers.

We should realize that we do not need astronomically overpaid professional athletes to live, they have proven to be the most useless part of our current culture. On the contrary, we would not be able to do without a shop assistant in our street, without doctors, police officers, teachers or garbage collectors. The eight billion inhabitants of the planet can continue to live happily only if we realize what is truly valuable and what is a complete waste of time, natural resources and finances. Let's appreciate the usefulness, let's rather pay decently for garbage collectors (without them, typhus would soon start to spread) and let only our children play in the hockey halls. I would like to live in such a civilization.

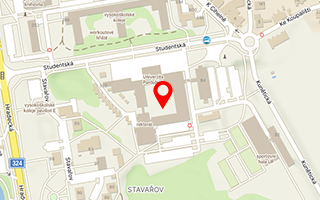

He works at the Institute of Historical Sciences, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, University of Pardubice. An expert on the social history of medicine, the history of spas and the cultural history of the 19th century, he comes from Šumperk. He studied history at the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy of the University of Pardubice. He obtained a Ph.D. diploma in 2013. In 2018 he completed a research internship at Birckbeck, University of London. He is currently leading a research team analysing changes in the relationship between physicians and patients between the 18th and 20th century. He is married and has two children. In the evenings, he searches in vain for sufficiently long cross-country trails in Pardubice, during the day he passionately cooks pasta for his children and dreams that the university salary will one day allow them to consume Argentine steaks.