Published: 24.09.2020

Milena Lenderová is a prominent Czech historian. Her main focus lies in the history of everyday life and history of gender in the 19th century. When I wanted to learn more about the beginnings of female emancipation, I did not hesitate a moment to decide who I would approach.

For centuries, women’s role was subordinated to that of men. A great progress has been made on the way to emancipation since then, but I can sometimes feel such subordination underlying any public debate on gender equality in the Czech Republic.

I agree but, in my opinion, it is actually women’s fault to some extent. There is nothing preventing them to oppose any attempts to treat them as being inferior. They have good education, better than men. A total of 40% of young females have graduated from university, which is 13% more than the percentage of young men; male university graduates prevail only among the elderly. Women need to raise their voice. Mercilessly. What I can also seen present in Czech society is something that I refer to as “sweaty male hood”, which involves the use of swearwords and stupid jokes about feminists. But such men will not stand up in any evidence-based debate.

We continue to perceive history as men’s history. Can you see any changes in this respect over the past years?

I think the statement needs some hedging. It is an undisputed fact that women were not in the limelight, be they rulers or artists. I do not think, however, that the reason is that men did not let them into certain walks of life. Any attempts by arts or literature historians to look for women commeasurable with William Shakespeare or Leonardo da Vinci would fail. Until women could acquire education, be it primary, higher, artistic or otherwise, they could not measure against men. And just realize how many centuries they lag behind...

In France, the beginnings of emancipation date back to the 17th century, in Czechland it was one century later. How difficult was it to promote emancipation in the then society?

Very difficult just as it is difficult to promote human rights in general. For female emancipation to have some relevance, it cannot involve one woman or several women only. Any emancipation movement must be preceded by understanding of the fact that people are equal and should be treated like that. What is ironical in Czech history is that before the revolution in March 1848, the Czech patriotic community encouraged women to acquire education or create works of literature. Czech society which was undergoing national emancipation wanted women to be educated and devote time to literature. The problems started only when the women, having the necessary education, wanted high-skilled work.

When history is taught, women are often portrayed as wives or mothers of important men that do not need much attention in a history class. Not to mention how women were often treated by such men, which is usually ignored altogether. Do you think that such stories should be also incorporated into history classes?

In my opinion, important and positive historical figures should be introduced with all their flaws. Pupils will find it more attractive.

Today, mothers feel a sense or responsibility (and even pressure) for education of their children. When did women start to make independent decisions about their children’s education?

This is also related to their education. A model of a mother who brings up her children personally and wisely and in line with the nature was developed by Jean Jacques Rousseau in Emile, or On Education in the mid-18th century. The book was first received well by young female aristocrats, even in Central Europe. It took a long time before it was also discovered by the Czech-speaking community; however, educated mothers tried to reconcile reason and emotion in education. Take the example of Božena Němcová, or Sofie Podlipská; the latter of them knew Rousseau’s book and was interested in education even in theoretical terms.

Infertility is a major issue nowadays. It is, however, discussed even in historical books, especially in noble families that wanted successors. Did the perception of infertile women undergo any development?

It was almost always a woman who was responsible for couple’s infertility. In well-off families, women tried to undergo some treatment, sometimes successfully, provided that it was the woman that suffered from infertility. Rarely, however, did the families adopt a child in order to have a successor. And if so, a child from a related family was adopted. Or a father’s illegitimate child.

Ironically, women enjoyed most freedom towards the end of their lives after their husbands had died. Provided that the husband had provided for the women, who would otherwise be entitled to the dowry only. Was it sometimes also the case that men who died prematurely left their wives in financial distress?

It is difficult to express this in quantitative terms, but this was the case mostly in war times. For example, the Austro-Prussian War hit really hard and left many widows facing existential issues. As well as many girls who would have obvious difficulties to find a partner of their age. It became evident that the women had no professional skills or qualification. This sparked a debate about the need for women’s professional qualification.

History records mainly deal with the lives of women from noble families, and slightly less so with the lives of townswomen. How about women living in the country? What is our knowledge of their lives?

You are right that it is easier to research the lives of women from noble families and townswomen. They were literate, some of them enjoyed writing, and left not only their diaries, but also letters. Such environments also provide us with image sources, such as portraits, images of interiors, sketchbooks with paintings by amateur painters. Recent years have, however, seen a remarkable development of research into the everyday life of people living in the country. This is mainly thanks to experts on historical demography and anthropology.

You carried out detailed research of diaries of women and girls from the 19th century, which provides a rather intimate insight into their personality. Which of the women appealed to you the most? Did you get any inspiration for your life?

Diaries are undoubtedly a fascinating source of information, but I do not think that any of the women could serve as inspiration for me. Some of them were closer to my heart, others (mainly the rebellious ones) even appealed to me. Those that I like the most are Božena Němcová, a writer, and Zdenka Braunerová, a painter. Both of them refused to comply with the gender limits, which had negative implications for them. The story of Božena Němcová was considerably more tragic, though. It may be explained by the fact that she met some of the requirements imposed by the society on women. She was a wife and a mother.

Did any of the diary heroines write about their maternal love? Or about the worries about the children?

I cannot recall any explicit reference to maternal love in the diaries. The women rather tried to escape the reality.

And how did they perceive their life? To be cyclical in nature, or rather linear, as we do?

Since I researched diaries of women from the 19th century, and part of the 20th century, they already perceived their life as linear. On the other hand, they did not touch upon the issue much. They did not do much planning.

You claim that most of the women who wrote a diary imagined that their diaries may be read by their parents, tutors or even readers in the future. That is why they tried to come across better. They tried to show their personality as they wished it to be. Thinking about that, it may be similar to what we have seen over the past few years on social media. Did women in the past also wish to appeal to the people around them?

You may put it like that. The only difference was that it was not about appeal to the public, but to the people around them should they encounter the diary. The diaries often (though not always) involve self-stylization and sometimes even self-censorship. This applies, however, in the same extent to diaries written by women as well as men.

During today’s pandemic times, we cannot ignore the fact that such situations were commonplace for women in the history. Wars, epidemic, death of children or relatives. What do historical sources say about the way they came to terms with such fates?

People died in large numbers of plague and smallpox. The plaque episodes finished in the early 18th century. Smallpox did not disappear and was joined by cholera and other catastrophic diseases. People often perceived such epidemics as divine punishment which left them virtually helpless and desperate. They experienced fear and often attacked those infected. This applied to both men and women. With time, protective strategies such as better hygiene and vaccination appeared. And most importantly, a clear approach of the public authorities based on modern healthcare legislation.

Milena Lenderová

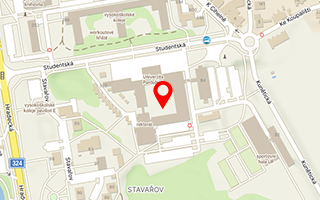

Professor Milena Lenderová is a prominent Czech historian. Her research focus lies in the history of Czech-French cultural relations as well as the history of everyday life and gender in the 19th century, which is also studied from personal documents such as diaries. She serves on a number of scholarly or artistic boards at a number of Czech universities, and teaches at the Department of History at the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy of the University of Pardubice. She has authored or ca-authored readable books on the topic of everyday life in the past. She addressed gender issues in the following books: Vše pro dítě! (2015), Dějiny těla (2013), Dcera národa? Tři životy Zdeňky Havlíčkové (2013) or K hříchu i modlitbě (1999). She has received a number of research and science awards; in 2015 she was awarded the Silver Medal for excellent research by the Senate of the Czech Republic.

The article is translated from Heroine.cz